By Clara Keane | February 15, 2018 | #WeAreArtTherapists

Charles Anderson, ATR-BC, as a pioneer of the art therapy field, witnessed the profession take root and grow. Retired at 77, he still works part-time at Stormont Vail West Hospital, serving clients in crisis and supervising students in the Emporia State University art therapy program. Anderson held many leadership positions in the AATA. He was the founding Chair of AATA’s Mosaic Committee (1990-94), was selected as a committee member on the first AATA Ethics Review Board and served two terms on the committee to review questions for the ATCB Certification Exam. The AATA awarded Anderson the Distinguished Clinician Award (2000) and the Multicultural Leadership Award (2008) in recognition of his contributions.

Charles Anderson, ATR-BC, as a pioneer of the art therapy field, witnessed the profession take root and grow. Retired at 77, he still works part-time at Stormont Vail West Hospital, serving clients in crisis and supervising students in the Emporia State University art therapy program. Anderson held many leadership positions in the AATA. He was the founding Chair of AATA’s Mosaic Committee (1990-94), was selected as a committee member on the first AATA Ethics Review Board and served two terms on the committee to review questions for the ATCB Certification Exam. The AATA awarded Anderson the Distinguished Clinician Award (2000) and the Multicultural Leadership Award (2008) in recognition of his contributions.

Mr. Anderson started his career in 1962 at Menninger Clinic in Topeka, Kansas, and was drafted a year later. He served two years (1963-65) at Fort Wainwright in Fair Banks, Alaska and then an additional two years in the Reserves (1965-67). His college classes at Washburn University pursing a BFA qualified him for the military assignment as a Recreation Specialist at the arts and crafts shop. He also coordinated the arts and crafts shops of the missile sites. His duties were to teach photo dark room procedures, ceramics, and jewelry making. Much of the jewelry work included lapidary work with Alaskan jades mined nearby. After discharge, he served in the Army Reserves and was assigned to a General Hospital Unit as an Occupational Therapist Assistant (there was no designation as art therapist in the military) and worked with people who were injured in Vietnam and suffered severe disturbances. He additionally had a private contract to teach painting and art history to for the Officers’ Wives Organization. After his service, Anderson completed his BFA from Washburn University (1970).

He worked at Menninger Clinic together with Bob Ault, HLM, ATR-BC and Don Jones, HLM, ATR, AATA Past President (1975-79), who introduced Anderson to art therapy. In 1974, Anderson received his ATR through the Grandfather Clause, on the basis of the number of years he had been using the creative process in his therapy before official training was available for registration. In 1992, the Menninger Children’s hospital hired him as a registered art therapist to start their first art therapy program. Anderson took the ATCB exam and received his Board Certification in 1996.

Anderson has 41 years of employment at Menninger’s (1962-2003, with a military leave 1963-65) and clinical experience in art therapy in a range of settings, including the Adult Short Term Diagnostic and Treatment, the Adult Long Term unit, the Dual Diagnosis Treatment unit, the Children and Adolescent unit, and the Adult Professional Crisis unit. In addition to supervising student art therapy interns, Mr. Anderson was an adjunct instructor at Emporia State University, Avila University, and Washburn University, covering coursework including introduction to art therapy and the creative arts therapies, and cultural diversity and multicultural issues in art therapy.

Also an accomplished artist, his exhibition, Charles Anderson: My Art Therapy Journey was displayed at the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site in Topeka, KS in 2012. An online version of the exhibition featuring “works created to overcome the stress and struggle of a life lived through the civil rights movement” and is now available on AATA’s website.

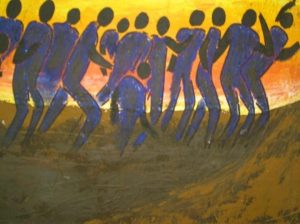

“The Struggle” by Charles Anderson. Acrylic Painting.

Artist’s statement: “The sun represents the overpowering pressure of opposition. Notice the arms and body postures for some individuals in the painting as they enter the struggle. One individual is about to overcome and in the process begins to sink into the earth. Another individual notices the person sinking and prepares to help the individual from sinking deeper.

Each individual in the picture represents many individuals who will one day overcome their struggles, but the impact leaves a sting that changes their view. A view of how they see themselves and the world around them for they will never be the same.”

When asked about how he has benefited from his AATA membership, Anderson says, “the professional focus.” Attending the AATA conferences and networking at the local level allowed him to continually expand his skills.

Anderson is keenly aware of the current popularity of art-making for self-care and its use in other professions, such as recreation therapy. He always tells his interns, “Be clear about your identity as an art therapist. Don’t blend it in with others who use art.” Anderson says the difference boils down to the main tool in therapy: “Art therapists use media as the focus, while many others may use art, but focus on talk therapy.” He clarifies, “Everyone is having people make art, but art therapists bring a different level of training and understand art as a medium.” He notes that a recreational therapist may direct clients to draw their feelings and then talk about them. However, in this way the client is directed immediately back to talk therapy. Anderson does not suggest that art therapists do not use talk therapy; rather, “art therapists discuss through media.”

Anderson offers as an example a technique he often uses with a group of people who have attempted suicide. He breaks down a common exercise into four phases: (1) rapport-building for preparation to task and function, (2) drawing the suicidal object or situation, (3) art therapy interaction and group support by redrawing the objects to make them safe, and (4) writing by patients sharing three written paragraphs about themes of hope, danger, and change.

Mr. Anderson contributed greatly in multicultural and diversity issues in the field. He recalls:

When I first started working on multicultural issues, people – a small segment of the AATA membership – said I was dividing the AATA by spending too much time focused on the differences between us. They used to say, “Underneath the pigmentation of our skin, we are all the same.” I would call this denial. I used to ask, “Well, how would you identify me? Would you identify me as male?” They would say yes. “As six feet tall?” They would say yes. But finally they would say, “I would not think of you as a black man.” I would ask them, “How can you identify me in all these ways yet remain so uncomfortable with my racial identity?”

While diversity and inclusion continue to be important topics in the world and in this field, Anderson notes the improvements he has seen. “Judy Rubin was very helpful as President [AATA President 1977-79] regarding these issues,” he notes. He further recalls that during the last AATA conference he attended in Dallas (2009), practicing with cultural competence was a major theme. This he found very important because he witnessed, too often, individuals being misdiagnosed or labeled treatment-resistant simply because they came from different cultural backgrounds.

In one instance, he remembers a Japanese client participating with a recreational therapist, but staying in the back of a group. Her cultural background regarding roles of authority and group members may have been misinterpreted by the therapist and resulted in the client’s being written up as “reluctant to accept interpersonal camaraderie.” Having worked mostly in treatment teams that were ninety percent or higher Caucasian, Anderson shares the example of an adolescent client from a low socioeconomic status and black community being labeled as treatment-resistant because he would not easily open up. Anderson understands what so many therapists did not: there is an unwritten rule among those of a low socioeconomic status not to share one’s inner thoughts and feelings with others or they will be used against you.

While Mr. Anderson has seen tremendous progress from the study of cultural competence, he acknowledges that this is still a real problem, and in some client groups, it may have gotten worse. One area he sees this especially often today is among adolescent clients who see gender differently than their therapist. “I see that quite a bit, disrespect when dealing with someone who sees gender differently.”

When asked about his hopes for the future of the profession, Anderson says, “I hope that we can just continue what we have done – separate ourselves from those who use the art therapist title without our quality of patient care.”