June 11, 2024 | By Magdalena Karlick, Ph.D-c, ATR-BC, LPCC, New Mexico

Your client or supervisee:

starts dating your student…

is good friends with one of your mentors…

is working with your therapist…

their good friend offers your partner a job…

they know each other well…

they date each other.

These connections evolve over time, some are unknown to the therapist/supervisor at first, some don’t exist… yet.

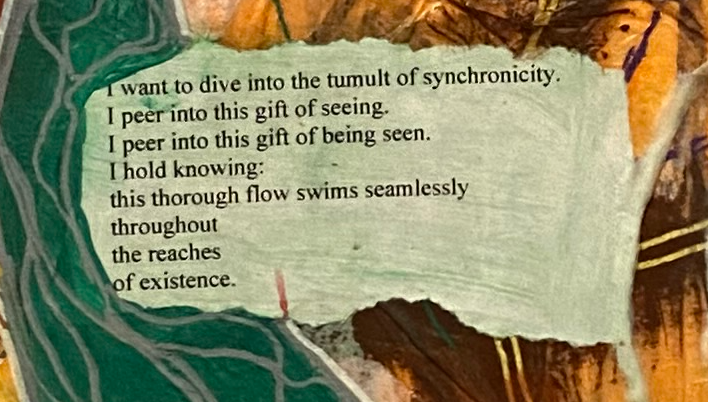

Magdalena Karlick, excerpt from “Over the Pond” 2024

In small queer* communities there are many overlapping connections: queer therapists, supervisors, and educators navigate multiple relationships among clients, supervisees, community members, as partners, friends, co-workers, exes, and family members (Everett et al, 2013).

Some queer therapists advertise this identity marker, as well as others (including BIPOC, neurodivergent, disabled, etc) to draw in clients and supervisees who have relatable lived experiences (Everett et al, 2013; Gormas, personal communication, August 6, 2020). Many LGBTQIA+ / Queer clients search for practitioners who identify similarly. The lived experience offers the potential for a deeper connection and understanding of small community dynamics, queer perspectives, and marginalized experiences (Jeffrey & Tweed, 2015).

Community overlaps and relationship intersections are not just found in the (multi-dimensional) queer communities of small towns / cities. I have had many roles in the small city that I live and work in: I went to and taught at for a decade the only graduate school for Art Therapy and Counseling in the city; I was the art director of a local organization that brings Palestinian and Israeli youth together to the city; I have been a school counselor at a small private school (Pre-K – 8th grade); I worked at an organization that provided housing and health services for displaced and unhoused youth, as well as offered counseling services for families involved in family court; and I am the mama of children in the schools in the city.

These public roles have encouraged the practice of being myself all the time, as well as the practice of humility when it’s my responsibility to repair an overstep.

Often, I know the people that they are bringing into the space, I may have worked with them in the past, know who their partner is, or they may have been a former student.

It has been rare that the intersection of relationships is concerning enough for me to say, “no, our circle is a little too small, let me refer you to another therapist [or supervisor].”

Clients bring friendship, workplace dynamics, heartache, school, and dating escapades to the therapeutic space. Often, I know the people that they are bringing into the space, I may have worked with them in the past, know who their partner is, or they may have been a former student. It has been rare that the intersection of relationships is concerning enough for me to say, “no, our circle is a little too small, let me refer you to another therapist [or supervisor].”

That being said, I have colleague-friends who have experienced romantic partner betrayal that has included friends of supervisees. And there are a couple of exes of mine who if they showed up as best friends, new lovers, or a close family member of a client, I would need to gracefully bow out of offering services. These intersections of “multiple relationships” or these “mine field(s)” (Zur, 2000) can be tricky to navigate.

The ATCB Codes and Dual Relationships, Cultural Competency, and Humility

ATCB ethics codes (2021) prohibit relational choices that have “exploitative” consequences and/or abuse the power dynamics that are present in therapist – client, supervisor – supervisee, and teacher – student relationships (see “Professional Relationships” 2.3.1 – 2.3.12). Small community dynamics are governed by standards of conduct related to confidentiality and privacy (2.1.1 – 2.1.12) as well as the guidelines related to integrity and humility (see “Competence & Integrity” 1.2 – 1.2.12). These codes hold the nuances of the therapeutic relationship in small communities within the context of cultural humility (Jackson, 2020) and local community standards.

It is important that we have conversations with our colleagues, students, clients, supervisees, partners, friends, family members (of course keeping confidentiality a priority) about boundaries, choices, and privacy, “If we identify as marginalized and belong to a marginalized community, we can’t keep avoiding dual relationships — we need to start thinking about them as something that are expected to happen” (Goerdt, personal communication, June 9th, 2024). Honesty, self-reflexivity, community care, interpersonal compassion, self-love are all important practices when navigating these layers of relationship (MacWilliam et al, 2019; Van Den Berg & Anderson, 2023).

Community participation is an important aspect of queering one’s personal and professional lives: engaging in conversations about shared community concerns regarding access to services and safety, local and global politics, as well as attending queer dance parties and events. This “queer ethos of care” (Anderson, 2021; Van Den Berg & Anderson, 2023) may be outside the dominant comfort zone in the Art Therapy field.

To explore the nuances of this topic, I sorted through old artwork and special collage images. I tore, pasted, painted over, drew on, scratched out, and let drip. >

I then recorded myself speaking about what I see in the image and created a spoken poem. >

Attending to the process of creating, the steps, and the metaphors offers me insight (Abbenante & Wix, 2015), and helps me to make clearer professional decisions.

Below are some art interventions that you can use to support your exploration of small community dynamics, and to create a compass to navigate professional ethical decision making (Frame & Williams, 2005; Hauck & Ling, 2019; Hervey, 2007).

Art Interventions to Explore Small Community Dynamics

1. Using Mod Podge, layer tissue paper and collage images related to your personal and professional relationships. What shows through the layers? What is hidden?

2. Use oil pastel to draw symbols related to your various community roles, and/or symbols to represent clients and community members; connect these symbols through smearing the oil pastel together, making them meet. What happens? What do you see?

3. Sound & Visual Art Response: Use Voice Memo or similar app to record words/phrases related to these explorations. Copy these saved recordings into Garage Band (or similar app), and layer them together in different tracks, creating an audio poem. Play the poem and use any visual art material to create an aesthetic response to the poem.

4. Visual Art & Movement Exploration: Visually represent community connections that you have with your clients/supervisees. Follow the movements that you create visually, with a movement of your body for each connection. Notice where the ease is and the joy as well as if there is doubt or discomfort. Journal what you notice (2 min timer works!).

Text of Poem:

Over the Pond

I tore up pieces

I tore up pieces of what once was

layers glued together I can see through parts of them

smearing paint

ripping out shapes from the past

pushing forward

rip them out

over the pond the water is a mirror reflecting the sky**

who dies without grieving***

the light

the lights is here

there’s a swirl

there’s a holding

there’s together

butterflies flap through the mandorla

staircase: a ladder of boundary

layers of tissue paper moving up

moving up towards

it’s not done yet

we’re here together

navigating complexity, beauty, mess, love, loss

who dies without grieving

over the pond the water is a mirror reflecting the sky

* I am using the term “queer” as an umbrella term for LGBTQIA++. This term is being repurposed as an inclusive term, rather than a derogatory term. I realize that for some folk in the LGBTQIA++ community this term has yet to be accepted due to the painful history it holds.

** From: Messner, K. and Neal, C. (2017). Over and under the pond. Scholastic, Inc.

*** From: “Yerba Mansa (Anemopsos Californica)” as found in a collage scrap from We’Moon (year unknown)

About Magdalena Karlick

Magdalena Karlick, Ph.D-c, ATR-BC, LPCC lives in Santa Fe, NM, O’Gah P’Ogeh Owingeh, the unceded territory of Tewa-speaking people. Her private practice, “Our Imaginal World,” offers individual and group supervision, Community Health Consultation, art installations, and therapeutic support.

Her new podcast “Belonging & Boundaries: An Arts-Based Approach” features interviews with educators in the art therapy, creative arts therapy, and expressive art therapy fields.

Stay tuned for a 2-hour CEU event expanding on her 2023 blog post “Belonging Is Being Seen.”

Magdalena is queer, of mixed heritage, a mama, and holds many privileges. For more information: www.ourimaginalworld.com

References

Art Therapy Credentials Board, Inc. (2021). Code of ethics, conduct, and disciplinary procedures. https://atcb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/ATCB-Code-of-Ethics-Conduct-DisciplinaryProcedures.pdf

Abbenante, J. & Wix, L. (2015). Archetypal Art Therapy. In D. Gussak & M. Rosal (Eds.) The

Wiley handbook of Art Therapy (pp. 37-46). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Everett, B., MacFarlane, D., Reynolds, V., & Anderson, H. (2013). Not on our backs: Supporting counsellors in navigating the ethics of multiple relationships within queer, two spirit, and/or trans communities. Pas sur notre dos: du soutien aux conseillers qui doivent naviguer éthiquement dans les relations multiples au seindes communautés gaies, bisexuelles, et trans. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 47(1), 14-28

Frame, M.W. & Williams, C.B . (2005). A model of ethical decision making from a multicultural perspective. Counseling and Values, 49(3), 165-179.

Harris B., Long K., MacWilliam, B., Trottier, D. (Eds.). (2019). Creative Arts Therapies and the LGBTQ Community: Theory and Practice. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Hauck, J., & Ling, T. (2016). The DO ART Model: An Ethical Decision-Making Model Applicable to Art Therapy. Art Therapy, 33(4), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2016.1231544

Hervey, L. (2007). Embodied Ethics. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 29(2), 91-108.

Jackson, Louvenia. (2020). Cultural humility in art therapy: Applications for practice, research, social justice, self-care, and pedagogy. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Jeffrey, M.K., & Tweed, A.E. (2015). Clinical self-disclosure, or clinical concealment? Lesbian, gay and bisexual mental health practitioners’ experiences of disclosure in therapeutic relationships. Counseling & Psychology Research, 15(1), 41-49. DOI: 10.1037/t20676-000.

Van Den Berg, Z. D., & Anderson, M. (2023). Queer Worldmaking in Sex-Positive Art Therapy: Radical Strategies for Individual Healing and Social Transformation. Art Therapy, 40(4), 188–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2023.2193660

Zur, O. (2000). In Celebration of Dual Relationships: How Prohibition of Non-Sexual Dual Relationships Increases the Chance of Exploitation and Harm. The Independent Practitioner, 20 (3), 97-100.