February 20, 2020 | Cheryl Doby-Copeland, PhD, ATR-BC, LPC, LMFT, HLM

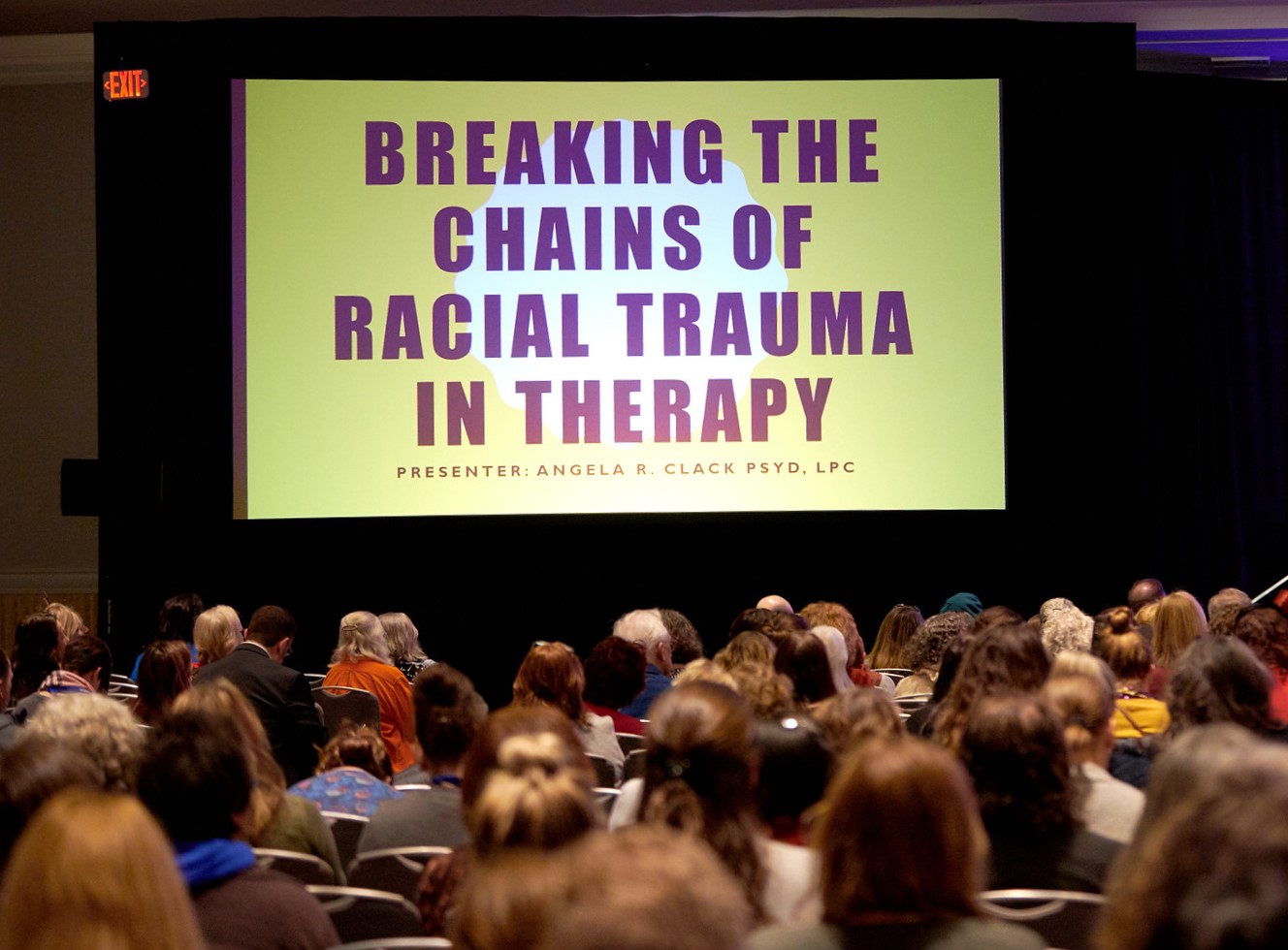

This post is part of the “Breaking the Chains of Racial Trauma in Therapy” blog series in honor of Black History Month, 2020.

The 400th anniversary of the arrival in America of the first enslaved people from West Africa validated my interest in the generational impact of racial trauma. The New York Times Magazine 1619 Project galvanized me to consider how historical racial trauma has not been a primary treatment consideration in my client caseload. Nikole Hannah-Jones, NYT investigative reporter and originator of the 1619 Project said it best, “If we are truly going to address the conditions that people live in now we have to deal with how they got here.”

I am pleased to join my colleagues in this blog series and to offer some terms and historical context important to guide the discussion.

1) Defining Racism

Race has long been a construct used in the United States to distinguish groups of people according to similar genetic and physical characteristics, however “race can also be viewed as a social category” (Shiraev & Levy, 2017, p. 5). Racism, described as: “Blatant and overt acts of discrimination that are epitomized by White supremacy, that denies people of color their equal rights and opportunities, and can include having hate crimes perpetuated against” (Sue & Sue, 2016, p.753) is considered a major stressor in the lives of people of color. Dr. Robert Carter (2007) stresses there are multiple definitions of racism:

- Individual racism – the belief in one’s superiority and members’ of the out-groups inferiority.

- Institutional racism – the unequal outcomes in social systems and organizations such as education, health care, employment and politics

- Cultural racism – the belief that the values/characteristics of one racial group are superior to that of other racial groups

- Avoidant racism – maintaining a distance or minimizing contact between members of the dominant and non-dominant racial groups

- Hostile racism – experiences meant to communicate the target’s inferior status due to their membership in the non-dominant group

- Aversive hostile racism – experiences intended to create distance with strong hostile elements after a person of Color has gained entrance into an institution/organization in which they were previously excluded.

2) Defining Racial Trauma

In the United States, hate crimes – attacks involving violent behavior motivated by prejudice, on the basis of race, religion, sexual orientation, or gender – are increasing (Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism, 2018). This only adds to the cumulative effectiveness of discrimination and institutional racism.

Racial trauma is comprised of the physical and psychological symptoms that people of color often experience after exposure to particularly stressful experiences of racism (Carter, 2007). These experiences with racism never exist in isolation; racial trauma is a cumulative experience where every personal or vicarious encounter with racism contributes to more insidious, chronic stress (Carter, 2007).

3) Understanding Racial Trauma in Art Therapy

As a clinician, I recognize that the effects of racism come from the social cultural environment and not from an abnormality within the individual that was exposed to racism (Carter, 2007).

Currently my clinical caseload primarily includes dyads of African American mothers with children who have been exposed to trauma. Dr. Clack (2018) indicated, “Sadly, many women do not know they have been traumatized because they have learned to live and function moving from one bad event to the next without stopping to think about the emotional, mental, physical and spiritual consequences of each hurt and disappointment” (p. 98). In my art therapy sessions, I find myself applying what Dr. Clack stressed: “It is important for the therapist to help clients make connections to the experiences in their lives and not have them blame themselves for victimization or exploitation that happened to them” (p. 107). This consideration is most important when the mother and child have been exposed to racial trauma.

In an effort to begin to address the symptoms of racial trauma with the families I serve, one of the measures I have found useful is the Philadelphia Expanded Ace Questionnaire. I’ve used this version of the ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences) questionnaire to assess for encounters with discrimination and racism to address in my clients’ treatment. Frequently there is a generational exposure to trauma among my client families. The resulting conversations revealed the experiences of grandmothers, and the “passing down” of survival behaviors and beliefs to their daughters/grandchildren (Clack, 2018, p. 103). Mother-child art making sessions have depicted the legacy of racial trauma, and its impact on the interactions within families today, so I can reframe their experiences and not have them blame themselves for the victimization that they experienced.

References

Carter, R.T. (2007). Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist, 35, 13 – 105. http://dx.org/10.1177/0011000006292033

Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism (2018). Report to the nation: Hate crimes rise in the U.S. cities and counties in time of division & foreign interference. Retrieved from: https://csbs.csusb.edu/sites/csusb_csbs/files2018%20Hate%20Report%205-141PM.pdf.

Clack, A. R. (2018). Women of Color Talk: Psychological Narratives on Trauma and Depression. Sicklerville, NJ: Clack Associates

Hannah-Jones, N. (August 18, 2019). The 1619 Project. New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america-slavery.html

Institute for Safe Families. Findings from the Philadelphia Urban ACE Survey. Available at: http://www.instituteforsafefamilies.org/sites/default/files/isfFiles/Philadelphia Urban ACE Report 2013.pdf.

Shiraev, E.B. & Levy, D.A. (2017). Cross-cultural psychology: Critical thinking and contemporary application (6th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Sue, D.W.& Sue, D. (2016). Counseling the Culturally Diverse: Theory and Practice (7th ed). New York, NY: Wiley.

Cheryl Doby-Copeland, Ph.D., ATR-BC, LPC, LMFT, HLM

Dr. Doby-Copeland has over 43 years of experience and continues to be fully employed as an art therapist. For the past 25 years, Dr. Doby-Copeland has worked for the D.C. Government Department of Behavioral Health in such areas as juvenile corrections, community mental health, public schools, and home-based services. In her current position working with young children and families, she is a clinician, manager, and supervisor. Dr. Doby-Copeland is a licensed professional counselor, licensed marriage and family therapist, and school psychologist. Dr. Doby-Copeland served as an adjunct professor in the Art Therapy Program at The George Washington University and originated the first course on multiculturalism in 1999.

Dr. Doby-Copeland has over 43 years of experience and continues to be fully employed as an art therapist. For the past 25 years, Dr. Doby-Copeland has worked for the D.C. Government Department of Behavioral Health in such areas as juvenile corrections, community mental health, public schools, and home-based services. In her current position working with young children and families, she is a clinician, manager, and supervisor. Dr. Doby-Copeland is a licensed professional counselor, licensed marriage and family therapist, and school psychologist. Dr. Doby-Copeland served as an adjunct professor in the Art Therapy Program at The George Washington University and originated the first course on multiculturalism in 1999.

Dr. Doby-Copeland has served three terms as Director on the American Art Therapy Association Board of Directors (1999-2001, 2013-2017) and served one-year as interim Speaker of the Assembly of Chapters (2018). Dr. Doby-Copeland received the Honorary Life Member recognition from AATA in 2018. She currently serves as a Director on the Art Therapy Credentials Board (ATCB).