By Irene Rosner David, Ph.D., ATR-BC, LCAT, HLM | January 27, 2016 | About Art Therapy

When asked to represent our field and organization on this panel during the Outsider Art Fair in New York, I was both honored and challenged. For decades I have welcomed opportunities to enlighten broadly and promote our work, however this was a new audience for me – outsider artists, outsider art gallery owners, arts-in-business people. I entered this project with the assumption that I would primarily explore aspects of Outsider Art and Art Therapy that may be perceived as overlapping, yet are different. This is a relationship I have pondered in the past, particularly having seen the infamous collection of L’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland.

I embarked upon the presentation by first succinctly defining art therapy and carefully excising it from the ‘outsider’ realm. I acknowledged aspects that are similar, such as art created by those untrained, outside of the mainstream art world and evocative of the creator’s inner life. As for differences, I was emphatic in explaining that it is the process that is prized, versus aesthetics and marketability. Artworks created in art therapy treatment may resemble that of outsider artists, but inherent is guiding the creative process to achieve higher levels of functioning and quality of life.

“Time After Time” – montage of patients’ clocks as a final image in Irene Rosner David’s presentation on the relationship between time and creativity at the Outsider Art Fair in New York.

In the course of preparation and building a power-point, I realized that panelists were asked for something more specific, i.e. how time is experienced and its relationship to creativity from the perspective of our realms. The Outsider Art Fair coordinator proposed the provocative notion in the digital flyer that time tends to stand still for the outsider artist, with repetition of imagery prevalent – whereas for the mainstream artist, the art generally moves or changes. This was thought-provoking in itself, but left me to ponder where the artist in art therapy falls into the concept. It was clearly to elaborate upon the way an artist in art therapy may evolve or progress personally, rather than artistically.

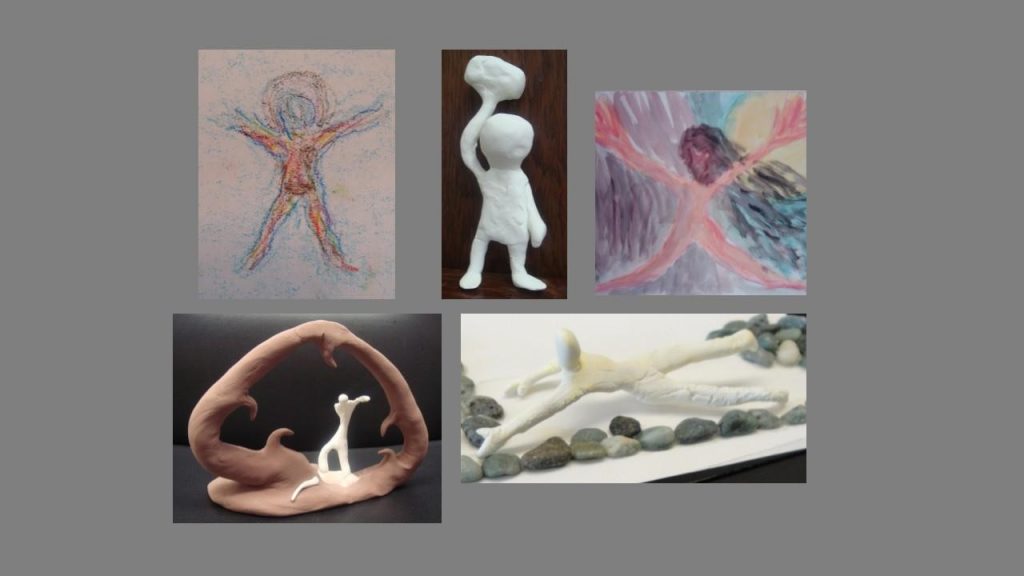

‘Frozen in Time’ – montage of images by traumatized patients to illustrate the ‘freeze response’

The question of time in the art therapy context caused me to delve into various perceptions of time and ways that they are expressed. The most apparent and general feature in art therapy is that change is supported over the course of time in treatment. Pulling from my expansive collection of artwork in medical art therapy, I showed how patients’ art progressed from barren and abstract to life-enhancing imagery, from fragmented segments to cohesive forms, from remote secluded stances to connectedness with life and others. Specific elements conveyed the emotional intensity of adjusting to disability and disease, pictorial variations of changed body and self-image and the poignancy of minimal time left to live with end-stage illness.

More concretely, I described how time itself is rendered or how one is altered in time. I discussed the ‘freeze response’ (Herman, 1997) as experienced in acute trauma, illustrated by drawings from my work, e.g. running from the twin towers, rigid as helpless prey confronted by a predator, or caught in place and time. I also described the prevalence of retrograde amnesia wherein brain injured and other traumatized individuals cannot recall the traumatic event (Joseph, 1990), with images conveying bewilderment and efforts to integrate past and present. Other time-related drawings were of clocks, in some cases implying the slowness or stoppage of time by patients in isolation, such as historic tuberculosis sanatoria or current infectious disease programs. Clock drawings are particularly telling as neuropsychological assessments (Freedman et al, 1994), which access the capacity for recall, sequencing and organizing in order to achieve a picture of this meaningful symbol. Cognitive deficits are revealed, but so too are the emotional fragility and uncertainty of time – in the metaphor and literally.

I felt the art therapy perspective was well received and a good balance to other panelists – a philosophy professor who spoke about the concept of time from a scientific lens, a gallery owner who promotes outsider art, and a well-known outsider artist who openly talked about his early traumatic experiences with a troubled father, as well as later medical issues. A gratifying moment during the culminating discussion was when the artist deferred to me saying he wished his father had the benefit of working with an art therapist – a recognition and reinforcement I did not expect. I commended his ability to re-direct his own issues into constructive form in art. However, indeed he and his father might have attained well-being more efficiently with the guidance of an art therapist. Quoting Dr. Kay Redfield-Jamison (1993, p. 123) I added:

“Creative work can act not only as a means of escape from pain, but also as a way of structuring chaotic emotions and thoughts, numbing pain through abstraction and the rigors of disciplined thought, and creating a distance from the source of despair.”

References

Freedman, M., Leach, L., Kaplan, E., Winocur, G., Shulman, K. I., & Delis, D.C. (1994). Clock drawing: A neuropsychological analysis. New York: Oxford University Press. Herman, J. (1997). Terror. In J. Herman, Trauma and recovery (pp. 42-43). New York: Basic Books.

Jamison, K.R. (1993). Their Life a Storm Whereon They Ride, In K. R. Jamison, Touched with fire: Manic-depressive illness and the artistic temperament. New York: The Free Press. Joseph, R. (1990). Neuropsychology, neuropsychiatry, and behavioral neurology. New York: Plenum.