April 28, 2020 | Barbara Robertson, LCPAT, ATR-BC

In this time of “Talking Heads” teletherapy, don’t forget that you and your client both have a body, one that can be utilized in the process of making art, and perhaps more to the point, looking at art and perceiving some of what the art has to say.

My first telehealth session for art therapy was scheduled with a new client, “Jan” (not her real name), whom I had seen only twice previously in my office. She began therapy with me just as word was beginning to spread that the Coronavirus had arrived in the United States. Some schools were closing, but serious social distancing rules had not yet been established.

I had struggled with when to begin limiting my sessions to remote contact. I felt I should err on the side of caution to protect myself, my family members and my clients from potential exposure to the virus. But how could I provide art therapy without offering the encouragement, the space, and the materials that came so easily to hand in my warm cozy space?

So it was with some hesitation that I approached those first telesessions. I offered my clients the gamut of the newly-approved technologies, including an ordinary phone call, FaceTime or Skype, or some of the videoconferencing apps. Jan chose a phone call. She is a young teen, with a great deal of anxiety and perfectionism. I guessed that the call, with no opportunity for being seen, would suit her reserved manner best. And I worried that lacking that visual window into her world would hamper my process as an art therapist.

What unfolded with Jan in this first phone session soon put me at greater ease about how the whole art therapy process might proceed. I began to realize that a different kind of connection might transpire over the phone, in a way that face-to-face contact in the closeness of my office might not support.

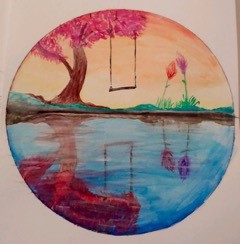

Jan had shown skill in drawing and watercolor in our second session in my office, when she had sketched a scene within a circular boundary drawn on the page. I had asked her to show the feeling of a “safe place,” where she felt she would be comfortable, accepted, and calm. She had begun with apparent ease but by the end of the session she was unhappy with her work. To me, though, it clearly conveyed tranquility. She took her work-in-progress home, hoping to improve on it on her own during the next week.

Watercolor by my client “Jan” (not her real name) , artwork and story shared with release.

That following week, our phone session got off to a somewhat awkward start, with Jan responding vaguely to my queries about her week, the impact of the changing pandemic situation, and her schoolwork, reportedly a source of distress. My client reported that she had made a couple of attempts to complete a drawing like the one she had begun in our second session, but was still not fully pleased with any of her attempts. She offered to show me the one she felt was finished “enough” by texting a photo of it to my phone.

It was then that our session spontaneously evolved into a three-way conversation between the client, myself, and her artwork. Here’s how it happened. I transferred the photo of Jan’s artwork to my laptop so I could see it better. We looked at the painting together from our separate places, and began to talk about what we were seeing.

When I look at art, I drop into my body and become mindful of my own internal sensory experience. It lets me feel the image in a way that feels more whole, more connected, more knowing than looking with my eyes alone. Early training in drawing taught me to see gesture not only in a model’s pose, but in many other things as well. Buildings, trees, flowers, vehicles, clouds, terrain, everything visible can be seen as having a kind of stance. When you pause to take in the gesture of a person or an object, you begin to sense in your own body what it’s like to hold that pose. Your mirror neurons are good at this, connecting you to another’s experience in a way that nothing else can.

Photo by Barbara Robertson

I invited Jan to take in the gesture of the tree standing by the bank of a stream in her image. The tree, on the left side of the circular border, held a swing suspended from its largest branch. Two small flowers stood close together on the other side of the swing, which hung directly in the center of the scene. How might it feel to stand like that tree, to hold the sinuous curve of its trunk, or the arching of its largest branch overhead? How would it feel to the tree, to support the swing from its strongest branch? What would it be like to connect with the ground at the broad base of the trunk, with its wide-spreading roots? Jan was able to feel the stability of that tree, along with its flexibility and resilience in bearing the weight of someone in the swing, or maybe in the whirl of a windstorm.

We shifted our focus next to the two flowers blooming on the other side of the swing. My client experienced them as “friendly.” Their stems tilted toward each other, the blossom atop each stem close together, a single leaf on each stem reaching toward the other, as if greeting one another or putting their heads together in quiet conversation.

After exploring in this way, I then invited Jan to stand up, and while looking at the image, to stand in any way she felt that the image might suggest. To warm her up to the idea, I described how I might stand if I were doing that, and invited her to take in something about the quality or feeling that arose as she stood, or reached, or turned in response to what she was seeing. This client, in her personal reserve, might have felt too awkward or silly to do anything like that in my presence. In the privacy afforded her by our voice-only call, she seemed able to appreciate the kind of flexibility that this tree appeared to possess.

I invited Jan to enter into the scene she had painted. She placed herself on the swing, but facing away from the stream, and away from the assumed viewer. Instead she chose to imagine facing the sunset which gave the sky a soft orange glow. I prompted Jan to bring in what her other senses might notice as well, about the sounds of water or wind, of sun on her face, swinging or sitting still there on the swing, how warm or cool the air might be, and what that all added up to for her.

Jan took note of how calm and comfortable she felt in her imaginal presence in the place she had painted. I believe she felt empowered when she found that she could shift her emotional experience in that body-centered, sense-based way. She was able to feel that sense of peacefulness as a reality over that period of time. As the creator of the image, she can also know that she has a kind of intuitive wisdom that directed her to imagine and depict a scene that suited her need for calm and comfort.

In a way, this telephone connection of voice to voice, rather than face to face, helped me to rely on my body’s realm of experience as one of the fundamental instruments in my therapeutic toolbox. I encourage you all to remember you are there from the neck down, as is your client, even when all you see is your head and theirs on the screen, or as in my phone call, you can’t see them at all. Allow yourself to shift your view away from faces, and take in and explore a visual image as you work together.

Barbara Robertson, LCPAT, ATR-BC

Barbara has run a private practice in Annapolis, Maryland, since 2012, treating children, adolescents and adults with a wide range of emotional and mental health challenges. Through her llifelong work as an artist, she trusts in artistic expression as a rich and colorful path toward abundant energy, intuition and direction in life.

Barbara has run a private practice in Annapolis, Maryland, since 2012, treating children, adolescents and adults with a wide range of emotional and mental health challenges. Through her llifelong work as an artist, she trusts in artistic expression as a rich and colorful path toward abundant energy, intuition and direction in life.

She completed her art therapy graduate degree at The George Washington University, Washington, D.C. in 2001. For the first 15 years as an art therapist, she worked in acute and long-term inpatient psychiatric settings, at the Maryland Department of Mental Health and Hygiene and at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C. She has a special interest and expertise in attachment challenged children, who come from “hard places,” and the families who want to love them through their hurt toward healing.