March 22, 2021 | Elisha-Rio P. Apilado, BFA, RBT and Zachary D. Van Den Berg, BFA

Two related but equally concerning trends have emerged during the Coronavirus pandemic in the Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) community: the rise in violence and the rise in mental health care needs. Stop AAPI Hate, an organization created to track discrimination and violence against the AANHPI community during the Coronavirus pandemic, received reports of 3,292 incidents that occurred in 2020. New York City police recorded 28 hate crimes against Asian Americans in 2020, up from three in 2019. In addition, AANHPI seniors and young people in particular, according to the Asian American Federation, have long had some of the highest rates of depression and suicide. They are now facing new racial trauma and a host of mental health issues stemming from the pandemic.

This response blog post is a plea for art therapists to intervene and recognize that our services can have life-or-death consequences, especially for the AANHPI community.

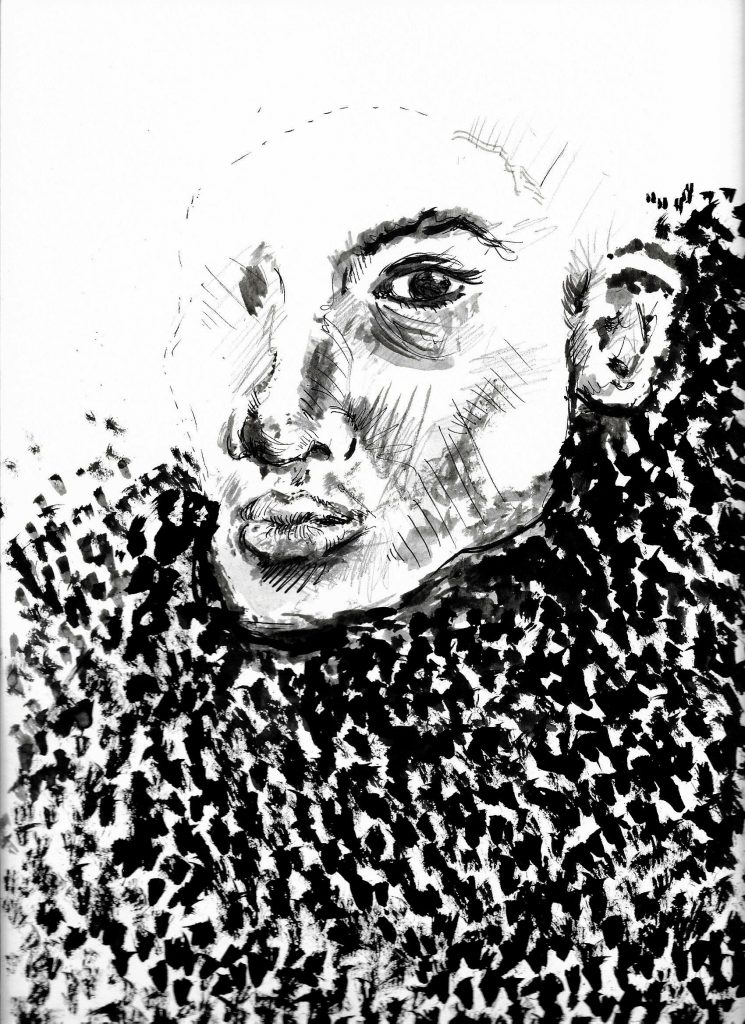

“Still Invisible,” by Elisha-Rio P. Apilado

Artist statement: A reflection on the recent Anti-Asian hate crimes, police brutality, and the ongoing effects of being an “invisible minority.” The topic of social justice has a stigma, as does mental health within our society. As individuals with privilege, we are able to voice our opinions and have greater access to a number of resources. So, it’s our responsibility to keep informed and educated on how mental health and social justice lives within other cultures.

Centering the History of Anti-Asian Injustice in the United States

There is a long history of the injustices within the Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) community that have been erased from the American narrative: the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which restricted immigration from Asia, stemmed from perception that Chinese immigrants were the source of diseases like smallpox, leprosy and malaria, and were taking away jobs from white workers; the 1942 order that led to the internment of more than 120,000 Japanese people, regardless of citizenship; and the violent murder of Vincent Chin, a Chinese-American in the Detroit area in 1982 by two men frustrated with the rise of Japanese automakers. Even today, the murders of Angelo Quinto, the victims of the domestic terrorist attack in Atlanta, and countless others who have been harmed from rising anti-Asian hate crimes remind us that if we continue to remain silently complicit we become participants in this legacy of violence against AANHPI communities.

Social Locations of the Authors

As emerging art therapists committed to social justice, we believe it is the ethical obligation of the larger systems, which govern our personal, professional, and cultural lives, to explicitly recognize, name, and disrupt inequitable statuses of dominance caused by White Supremacy. With solidarity from the American Art Therapy Association (AATA), we hope that this call to critical action will inspire practicing and non-practicing art therapists to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion within our areas of influence. As authors, we recognize we are each located on differing axes of power—as a ciswoman of color and a white, masculine-presenting individual. In collaborating on this shared resource, we are practicing active allyship: centering marginalized identities and de-centering those already in the mainstream.

Performative activism, or going through the motions of supporting an issue to increase one’s social capital, has clouded democratic approaches to genuine activism. This is especially true at this moment, as we stand up against anti-Asian bias and violence, and more broadly against White supremacy. As Vice President Kamala Harris tweeted, “Hate crimes and violence against Asian Americans and Asian immigrants have skyrocketed during the pandemic…We must continue to commit ourselves to combating racism and discrimination.”

The Art Therapist’s Ethical Obligation to Cultural Humility and Social Justice

As art therapists, we need to integrate a culturally humble stance in theory and practice, as we actively display solidarity and radical care towards our AANHPI clients and colleagues, as explained in AATA’s Art Therapy Multicultural/Diversity Competencies (AATA, II.C.3., 2011). It is our responsibility to stay informed and actively seek out resources to educate ourselves and others on how to show up in solidarity and camaraderie with our AANHPI peers, colleagues, and clients. The AATA DEI Committee’s value statement during the Coronavirus pandemic upholds this imperative by stating that “all people deserve equal access to high-quality healthcare, including mental health care. As the clients we serve come from diverse backgrounds, advocating for health parity and its impact on their lives and well-being is essential.” Even further, the Art Therapy Credentials Board encourages art therapists “to recognize a responsibility to participate in activities that contribute to a better community and society, including devoting a portion of their professional activity to services for which there is little or no financial return” (ATCB Code of Ethics, Conduct, and Disciplinary Procedures, 1.5.6).

AANHPI, Stigma, and Implications for Art Therapy

According to Mental Health America, the AANHPIs are the least likely racial group in the US to seek mental health services. The stigma around mental health care may stem from cultural norms of putting family and community first, community pressure of avoiding shame, living up to the model minority myth, and lack of awareness about treatment. The low rate of seeking mental healthcare makes the recent anti-Asian violence all the more vital for art therapists to address. Art therapy’s capacity to circumvent initial client reticence toward mental health care has major implications for the community. AATA President Dr. Margaret Carlock-Russo says in the AATA Statement on the Georgia Shootings and Rise in Anti-Asian Violence During the Coronavirus Pandemic, “It is imperative that we listen to and support our AAPI clients, colleagues, and community members as they navigate racial trauma and the stress and fear that come with being targets at work, on the street, and throughout their daily lives.”

Avoiding performative activism is equally important in fighting the pervasive stigma surrounding mental health for AANHPI communities. We must challenge our implicit biases about the AANHPI community—and initiate constructive conversations to address the mental health crisis within the community.

Intragroup Community Building

A vital part of intracommunity advocacy and education is to inform the AANHPI community of alternatives to relying on the police for mental health crises. It is also critical to examine how colonization has impacted the community’s response to mental health, which has perpetuated the harmful narrative of the model minority myth. While it is understood in AANHPI collectivistic culture that it is best to avoid confrontations with others and maintain harmony, sometimes this characteristic needs to be renegotiated and disrupted to preserve the physical, emotional, and mental well-being of AANHPI individuals. AANHPI art therapists, and art therapy students in particular, also need to (re)prioritize their own mental health.

The effects of colonialism in older generation AANHPIs have also seeped through to younger generations, skewing perspectives on who can truly help AANHPI communities in a crisis, especially in a mental health situation. While the immediate reaction may be to call 9-1-1, as this has been the norm taught to us, AANHPIs may need to unlearn this reaction, especially in response to a mental health crisis, and better inform themselves on other ways to call for help, such as a mental health crisis hotline. There is also a strong need to provide accurate psychoeducation on what a mental health crisis episode may look like. Such community-based interventions can prevent future situations like what Angelo Quinto’s family experienced. Mr. Quinto was murdered by police who were responding to a call by his family during a mental health crisis.

As a member of the AANHPI community, I (Elisha) have to acknowledge how colonization has affected the way I walk through this world, feeding into the model minority narrative that was put on me. While it is understood that our collectivist culture sets us to avoid confrontations in order to maintain harmony, we need to re-evaluate if this characteristic is something to be reconsidered and disrupted when it comes to preserving the physical, emotional, and mental well-being of the people in our community.

AANHPI art therapy students and professionals need space for intragroup community building. As Miki Goerdt notes in Asian Art Therapists: Navigating Art, Diversity, and Culture, “Asian art therapy students have few opportunities to consult and explore with other Asians in the same field […] This contributes to the creation of many unanswered questions that need exploration and clarification when an art therapist enters into the workforce” (p. 127). So, we ask, when continuous collective trauma is sustained against Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islanders—specifically throughout the COVID-19 pandemic—how can these individuals grieve communally and share their lived experiences within the safety of shared identities? The absence of space where AANHPI art therapy students and professionals can process and commune over this shared collective trauma begs the question: who has the power to create these spaces within the art therapy profession and who has access to benefit from these services?

We urge AANHPI allies to support crafting these spaces, and open discourse around ethnicity and immigration and its impact on clinical practice. We are eager to have dialogue on how, as allies, we can actively promote more significant diversity, equity and inclusion— and as students and professionals committed to social justice, we can most effectively address racial trauma in the AANHPI community.

Below, we share some suggestions to start this conversation and encourage you to seek out more information and resources specific to your region so that collaboration and active allyship can begin.

Resources

Get Started

- Asian Mental Health Collective – “It is the mission of the Asian Mental Health Collective to normalize and de-stigmatize mental health within the Asian community” https://www.asianmhc.org

- Stop AANHPI Hate – “The center tracks and responds to incidents of hate, violence, harassment, discrimination, shunning, and child bullying against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the United States.” https://stopAANHPIhate.org

- Asian American Psychological Association – “Advance the mental health and well-being of Asian American communities through research, professional practice, education, and policy” https://aapaonline.org

- Places to Donate

Advocate for Equitable Access to Care

- Policy proposal to eliminate linguistic barriers to care

- Mental Health Interpretation

- Transcultural Diagnostic Terminology

- Supporting Your AANHPI Colleagues

- Anti-Hate Crime Legislation

Be an Ally

Practice Cultural Humility

- Mental Health American: Asian American/Pacific Islander Communities and Mental Health

- National Alliance on Mental Illness: Asian American and Pacific Islander

- American Psychological Association: Resources from the Ethnicity and Health in America Series

- American Psychiatric Association: Diversity & Health Education: Asian American

- Fact sheets on a variety of issues facing AANHPI communities

- Art Therapy Education

- Call for Diversity

- Cultural Humility in Medical Art Therapy

Center AANHPI Voices in Art Therapy

- Christine Wang, ATR

- Girija Kaimal, EdD, ATR-BC

- Melissa Raman Molitor, MA, ATR-BC, LCPC

- Miki Goerdt, LCSW, ATR-BC

- Young Imm K. Song, PhD

- Ashley Abigail Gruezo Resurreccion

- Eunice Yu, MS

Safety Tips

About the Authors

Elisha-Rio P. Apilado, BFA, RBT

Before switching careers, Elisha-Rio worked ten years in marketing as an art director and graphic designer. After a couple of years working as an art teacher at homeless shelters and leading community art projects, she recognized the power of what art could do for an individual’s mental well-being. And that’s when she found art therapy.

Before switching careers, Elisha-Rio worked ten years in marketing as an art director and graphic designer. After a couple of years working as an art teacher at homeless shelters and leading community art projects, she recognized the power of what art could do for an individual’s mental well-being. And that’s when she found art therapy.

Elisha-Rio currently attends Adler University in Chicago to earn her Master of Arts in Counseling. She will then continue to become a Licensed Professional Counselor and obtain a Registered Art Therapist certification. As an active advocate of mental health and the benefits of expressive art therapies, Elisha-Rio has spoken at several Ignite Talk Chicago events about reframing mental health stigmas, and she has hosted several art-focused self-care workshops with the American Institute of Graphic Arts and Creative Women’s Co. She recently joined the Asian Mental Health Collective to open up the Chicago Chapter to provide roundtable discussions concerning mental health stigmas within the Asian community. When she’s not working as a medical art therapy intern with cancer and stroke patients at AMITA Health or providing ABA therapy as a registered behavior technician, she is busily training at the dance studio.

Zachary D. Van Den Berg, BFA

Zachary D. Van Den Berg (he/him/they/them) is pursuing his Master of Arts in Counseling: Art Therapy from Adler University in Chicago, IL (expected graduation May 2021), and received his BFA at the School of the Art Institute (SAIC). Currently, he is President of the Adler Art Therapy Student Association, founder of the international online forums Art Therapy Students Associated and Queer Creative Arts Therapies, a member on the Multicultural Committee and the Membership Committee of the American Art Therapy Association, an Intern for Special Projects for the American Art Therapy Association, and the volunteer coordinator and Film Library Committee Member for Expressive Media Inc. He is currently interning at the Center on Halsted, an LGBTQ+ community center in Chicago.

Zachary D. Van Den Berg (he/him/they/them) is pursuing his Master of Arts in Counseling: Art Therapy from Adler University in Chicago, IL (expected graduation May 2021), and received his BFA at the School of the Art Institute (SAIC). Currently, he is President of the Adler Art Therapy Student Association, founder of the international online forums Art Therapy Students Associated and Queer Creative Arts Therapies, a member on the Multicultural Committee and the Membership Committee of the American Art Therapy Association, an Intern for Special Projects for the American Art Therapy Association, and the volunteer coordinator and Film Library Committee Member for Expressive Media Inc. He is currently interning at the Center on Halsted, an LGBTQ+ community center in Chicago.