May 17, 2021 | Miki Goerdt LCSW, ATR-BC

As May is Asian American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (AANHPI) Heritage Month, I have been reflecting on my work with AANHPI clients. I am an East Asian immigrant, a Japanese art therapist, and a clinical social worker. When I used to work at a local government’s outpatient clinic, I rarely encountered AANHPI clients. Then when I switched to private practice several years ago, the demographic of my clients changed. Now I see many Asian faces each week.

I am sharing several stories from sessions with my AANHPI clients, hoping that they give you some understanding of AANHPI clients’ lived experiences. (I have changed some details and refrained from sharing their specific ethnicities in order to protect their privacy.)

Sessions with my AANHPI clients

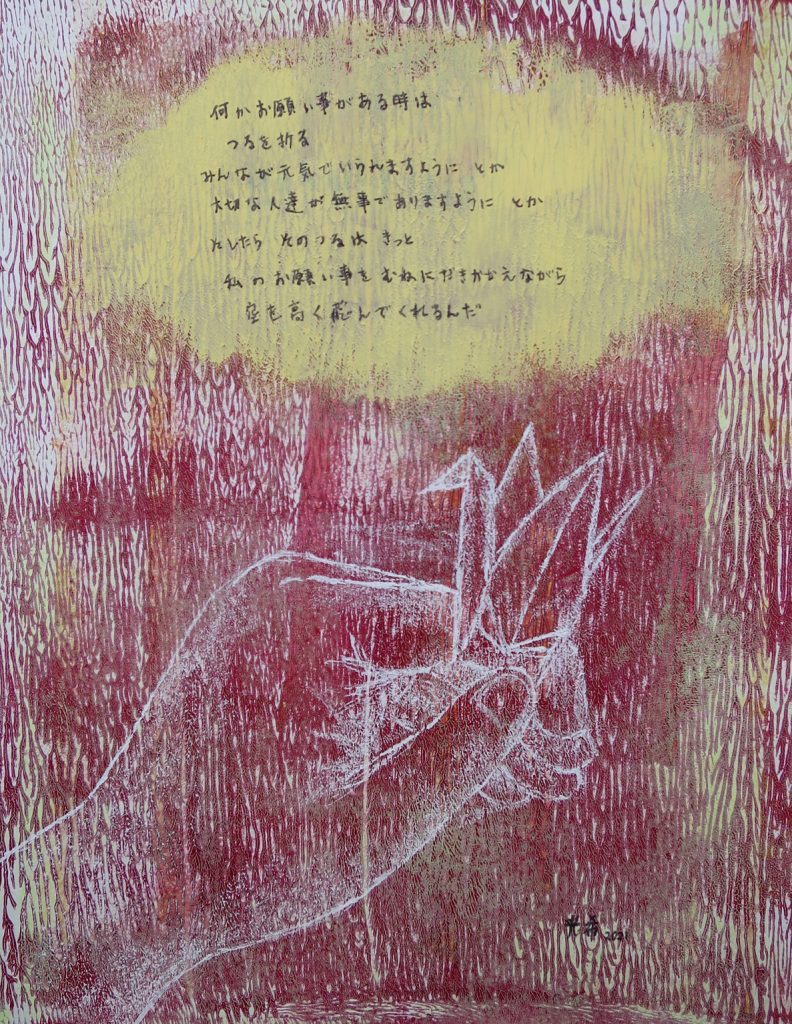

This image is an entry in my visual journal and a reflection origami. Using the concept of Senbazuru (“1000 cranes”) for making a wish, I sometimes fold paper cranes with my clients. The writing in the image translates: “When I want to make a wish, I fold a paper crane. Please let everyone stay healthy. Please keep my loved ones safe. The crane holds my wishes close to its heart, and it flies high in the sky as it carries my wish.”

“You shouldn’t have cut your hair short like that,” my older adult client says to me. She identifies as Asian, and she finds comfort in our shared Asian roots. Some of her trust comes out as an expression of advice to me. As her therapist, I receive it without challenging it or asserting my power as a therapist. As a younger individual, I am not only her therapist but also a recipient of my AANHPI older adult client’s wisdom when we sit in the same room together. As the client passes on her knowledge to me, she gains a sense of validation and purpose. The more I am willing to receive, the more she opens up.

An older Asian client shares her past memories with anger and sadness. She starts to share more of her life story as I validate her feelings— her struggle as an immigrant with limited English proficiency, difficult inter-racial marriage, and suicidal ideation. Knitting and sewing have been not only her vocation but also her coping mechanism throughout her life. In one session, she hands me a knitted washcloth as a gift. “This is for you so that you will remember me.” As I receive it, I wonder how much of her life she spent feeling invisible and forgotten.

Tears rolls down an Asian female client’s face as she writes a letter to herself in my office. The letter is sent to her past self who spent time in a predominantly White school years ago. There she felt inferior to White individuals and pressure to outperform them as a way to prove her worth. She writes of the fatigue that came with the effort to behave like a (White) American in order to be accepted. She reads the card aloud, with words of affirmation and understanding to her past self. I witness her words and emotions. I talk about the cost and pain of assimilation and share some of my own experiences with it, so she knows she is not alone.

An Asian female adult client says to me, “I just never felt pretty when I was in school.” When I ask, “Compared to whom?” my client replies, “Other girls.” “What race?” I ask. She tells me she felt ugly compared to other Asian girls in school and describes how she could never be like them: “I just felt so different. I didn’t know what group to place myself in. I didn’t know where I belonged.” At the end of the session, she voices some relief. “I didn’t know we can talk about race in therapy.”

“As an Asian woman, I know my words are not worth anything,” an Asian client says as we discuss the Atlanta shootings. Six of the eight victims were Asian women. Her statement in the session is provoked by the shootings, but I also notice it applies to her experience of marriage, feeling powerless under the power of her White American husband.

As I sit at my desk across the computer screen from a young Asian/NHPI client, I notice anxiety in her facial expression and voice. She worries about being with others and not being able to become intimate. I suggest we make Omamori (Japanese lucky charm). Hers looks like a chrysalis on the outside, and she stashes a folded orange butterfly made out of paper inside. “A symbol of transformation and hope for me,” she says.

I made this Omamori during a session to show my client how to make one.

Seeing my AANHPI clients from multi-layered perspectives

I try to show up for my clients as an art therapist as well as a human being. With AANHPI clients and other BIPOC clients, I keep their cultural rules in mind. I share more about myself—it is possible to do that and maintain effective boundaries. I talk about race and ethnicity with them. I notice and process how harmful stereotypes and discrimination affect them. I invite them to re-write unhelpful narratives in their inner voices, such as internal racism. I acknowledge with them how AANHPI communities at times discriminate against each other. I discuss how some AANHPI individuals (including our own family members sometimes) are conditioned to play the games of othering some AANHPI individuals as “not Asian enough” or labeling other AANHPI individuals as “a sellout to White people.” I use culturally familiar art forms with them, while being careful to avoid harmful cultural appropriation. I am constantly studying historical backgrounds of AANHPI communities in order to understand how my AANHPI clients are uniquely placed in this society. I try to get some knowledge on topics related to AANHPI clients’ lives—For example, what does it mean to be a war bride? Or to preserve the language? Why aren’t shootings and killings of Sikh people discussed much in the media? And how does limited English proficiency affect AANHPI individuals’ mental health?

I am mindful of the fact that being the same race/ethnicity is not enough for me to provide effective therapy with my AANHPI clients. My learning of humility and understanding over culturally appropriate therapy should never have an ending—neither should the reflection on my own racial/cultural identities within the context of the society I live in. I appreciate how my clients trust me and see me as someone with whom they can relate. It fills me with a pride to serve my own people and other AANHPI communities.

Additional readings:

- “Cultural factors influencing the mental Health of Asian Americans” – The Western Journal of Medicine

- “Why Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders Don’t go to therapy” – National Alliance on Mental Illness

- “Asian American/Pacific Islander Communities And Mental Health” – Mental Health America

- “LGBTQ+” – South Asian Sexual & Mental Health Alliance

- “AAPI LBGTQ Resources”– Asian American Psychological Association

- “How Can White Therapists support Asian American Clients?” – Psychotherapy Networker

- See No Stranger: Revolutionary Love Project – Valarie Kaur

Miki Goerdt LCSW, ATR-BC

Miki Goerdt is a Board-Certified Art Therapist and a Licensed Clinical Social Worker in Virginia. She has a private practice in Falls Church, Virginia and works primarily with older adults, BIPOC individuals, and immigrant individuals.

Miki Goerdt is a Board-Certified Art Therapist and a Licensed Clinical Social Worker in Virginia. She has a private practice in Falls Church, Virginia and works primarily with older adults, BIPOC individuals, and immigrant individuals.