February 26, 2020 | Jordan S. Potash,PhD, ATR-BC, REAT, LCAT (NY), LCPAT (MD)

This post is part of the “Breaking the Chains of Racial Trauma in Therapy” blog series in honor of Black History Month, 2020.

As a White art therapist who has worked cross-racially for almost my entire career, I am regularly reminded that there are always racial-social-political influences that enter into the art therapy relationship. My current work in an open art therapy studio at a drop-in center for runaway and homeless adolescents and young adults, most of whom are Black, reinforces three strategies for art therapists for understanding and responding to power differentials.

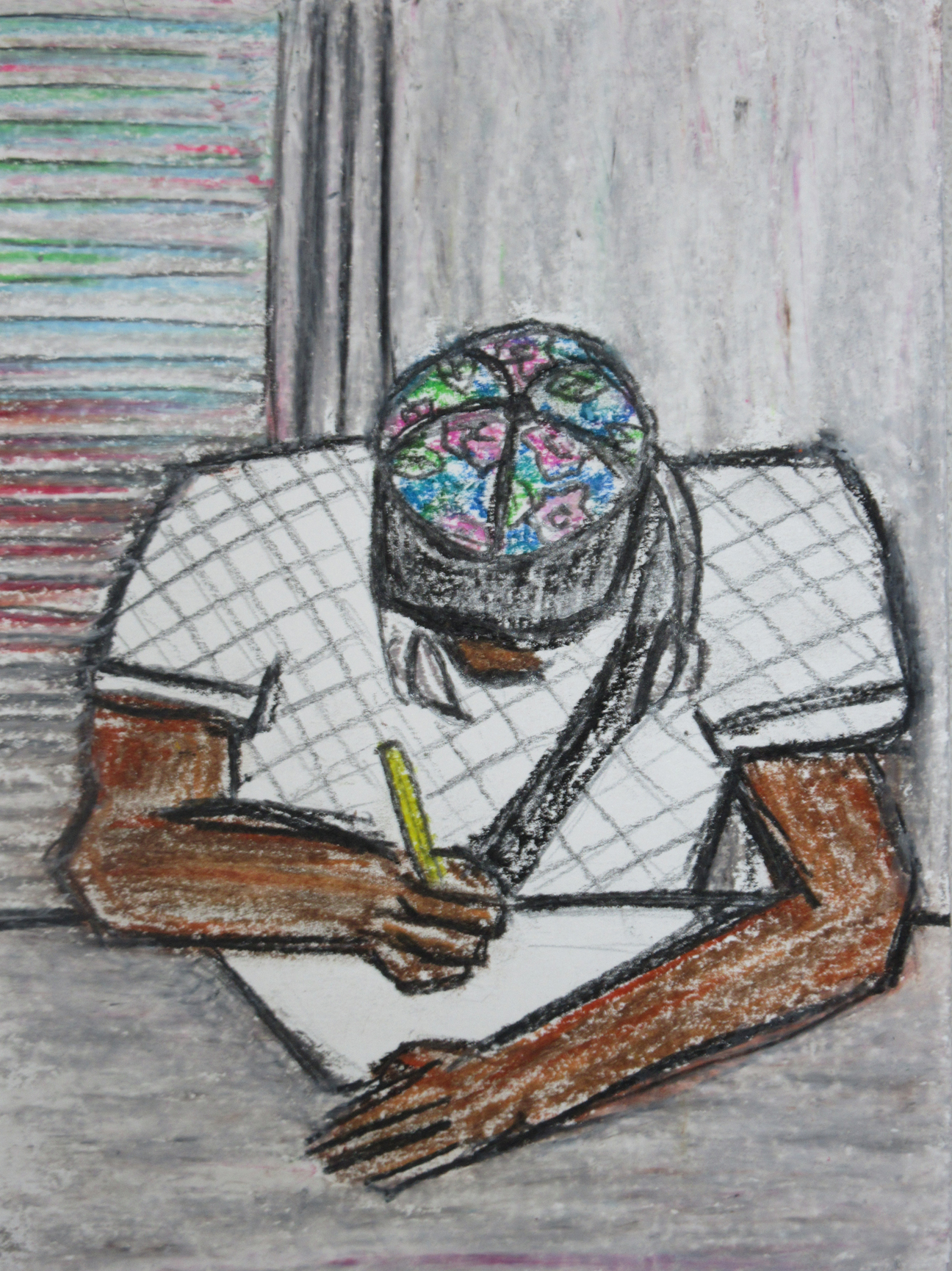

Client portrait response art by Jordan Potash

1) Develop an Anti-racist Perspective

Dr. Ibram X. Kendi (2019) and Dr. Robin DiAngelo (2018) teach that ignoring race, promotes racism. Actively confronting race-based injustices, promotes anti-racism. I apply their teachings by:

- establishing cross-racial rapport with each new client as their previous experiences with White people may inform expectations;

- assuming presence of racial dynamics as a factor in how clients and I react to each other;

- acknowledging distress may be perpetuated by racism and White supremacy – otherwise, there is a false assumption that current situations are only a result of personal choices rather than a product of discrimination, violence and systemic policies;

- stating my willingness to discuss how racial differences impact worldviews and experiences when the client is ready.

2) Re-examine Core Art Therapy Concepts

The mental health frameworks by Dr. Angela Clack (2018) and Dr. Kenneth Hardy (2013, 2016) offer ways to re-examine art therapy concepts through anti-racist paradigms.

- Metaphor: Clack describes psychological masks that Black women wear as an adaptive defense that conceals shame, vulnerability, and rage that results from interpersonal discrimination and systemic racism. Honoring the mask as a form of coping against racial trauma enacts Dr. Hardy’s insistence for Black clients to express themselves in self-chosen and genuine manners. Client metaphors allow for simultaneously concealing facts but revealing a truth.

- Studio: Clack cautions that the mask reinforces a compulsion to hide weakness or ask for help. Dr. Hardy observed how some Black clients sacrifice authenticity by censoring themselves in order to take care of White people who might find them threatening. One way to promote anti-racism is by creating a studio in which Black clients can rest their masks to the degree to which they feel comfortable.

- Art Materials: Emotional expression requires vulnerability. Dr. Hardy describes the pain of connecting personal experiences to racial trauma. Clack sites impediments to trusting White therapists as rooted in how Black people have been punished, shunned, manipulated, and killed for expressing their views. They both recommend moments for contemplative pauses. Experimenting with art materials may offer such a space.

- Witnessing: Witnessing in art therapy entails supporting a client to make meaning of their art. Dr. Hardy insists that therapists avoid a race neutral position when assessing or prescribing solutions. For example, Dr. Clack redefines depression for Black people as a “disconnection” from ancestry, body, and source of power (p. 42).

3) Pursue System Change

Adapting practices in one’s work merely accepts the reality of race dynamics but does little to challenge them. To fully serve clients, art therapists must advocate to reduce barriers to treatment and dismantle harmful institutions. Within the drop-in center, clients create semi-public works of how they want to portray themselves and homelessness. Aside from direct service, I volunteer with local and national organizations that pursue policies to end homelessness by eradicating systemic racism and poverty, such as Sasha Bruce Youthwork and the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival Art and Culture Committee. I am also a member of my university’s Faculty Learning Community on Black Lives Matter for continuous education and to help develop curricula resources across academic disciplines. Re-imagining art therapy theories and practices is just the first step for carrying a commitment to justice beyond the studio walls to the streets, legislative bodies, and voting booths.

References

Clack, A. R. (2018). Women of color talk: Psychological narratives on trauma and depression. Clack Associates

DiAngelo, R. (2018). White fragility: Why it’s so hard to talk to white people about racism. Beacon Press.

Hardy, K. V. (2013). Healing the hidden wounds of racial trauma. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 22(1), 24-28.

Hardy, K. V. (2016). Anti-racist approaches for shaping theoretical and practice paradigms. In M. Pender-Greene & A. Siskin (Eds.), Anti-racist strategies for the health and human services (pp. 125-139). Oxford University Press.

Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an antiracist. One World.

Jordan S. Potash, PhD, ATR-BC, REAT, LCAT (NY), LCPAT (MD)

Dr. Potash is Associate Professor in the Art Therapy Program at The George Washington University and Editor in Chief of Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association. For more information, podcasts, and articles, please visit www.jordanpotash.com.