By Clara Keane | May 11, 2017 | Children | Education

A girl feels disoriented and hopeless in her familial and social context. This represents her alone in a forest, standing in a puddle during the midst of a storm and approaching quick sand under a dark sky.

During the month of May, starting with the kickoff event on National Children’s Mental Health Awareness Day with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the AATA is highlighting topics related to children’s mental health in Art Therapy Today. Children benefit from art therapy in a variety of ways: for example, children with autism often find art a viable way to communicate; children with attention deficit disorders show improved ability to focus; children in cancer wards are soothed by art therapy. The list goes on and on.

However, art therapy is not only beneficial to children with special needs. One way to make art therapy accessible to every child is to bring it to the schools. An AATA staff member took the opportunity to interview an expert in the setting of school-based art therapy, both in the classroom and in program design, to discuss how children can use art therapy to reconcile and process the chaos of both the outside world and their internal selves.

However, art therapy is not only beneficial to children with special needs. One way to make art therapy accessible to every child is to bring it to the schools. An AATA staff member took the opportunity to interview an expert in the setting of school-based art therapy, both in the classroom and in program design, to discuss how children can use art therapy to reconcile and process the chaos of both the outside world and their internal selves.

Marygrace Berberian, LCAT, ATR-BC, LCSW is a Clinical Assistant Professor with the Graduate Art Therapy Program and Director of the NYU Art Therapy in Schools Program at New York University. Marygrace has established school based art therapy initiatives throughout New York City for at-risk children and families for almost 20 years. Currently, Marygrace is leading the advocacy efforts for the inclusion of creative arts therapies in public schools in New York State and is a doctoral student in Creative Arts Therapies at Drexel University. We asked Marygrace four questions about her work with children in the school setting. This is what she said:

Q1: How do school-based art therapy programs in public schools benefit the community?

A1: When a student struggles cognitively, emotionally, or behaviorally, schools are often the first to identify symptoms and are then charged to deliver intervention. Accessing mental health services is often too daunting and cost prohibitive for overwhelmed, at-risk families. School facilities are more often becoming the sole providers of mental health support.

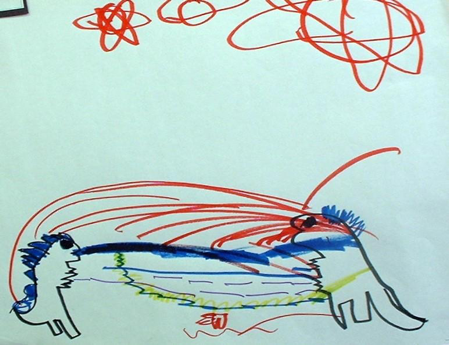

Art Therapy services in schools have effectively responded to the diverse and ever changing needs of students. Students have been aided by the capacity of art making to restore healthy functioning and provide mastery amidst feelings of helplessness. Art therapy presents an effective means to address these issues since students are offered an outlet to channel their anxiety and aggression into the art making process. The symbolic images that are generated allow students a capacity to express feelings and ideas regarding psychological conflicts and life experiences that are too emotionally loaded for verbal communication. When these issues are explored in the initial phase of treatment, there are usually more critical issues underlying the manifestations being observed in the school environment. Students are often discovered silently struggling with anxiety, depression, social difficulties and low self-esteem. Art helps students organize the chaos of their internal worlds and their often less than favorable realities.

As the students are a “captive” audience, treatment can be consistent and long term. Further, the art therapist can serve as the bridge between parents and teachers, fostering a more comprehensive and inclusive perspective on progress and the existing impediments. The seamless integration of art therapy services with other school services supports the students, teachers, and families to overcome obstacles and restore functioning.

- A child feeling vulnerable after 9/11 in his New York community equips himself with weapons and an army for battle.

- Fantasy and imagination are utilized to envision reconstruction following the devastation of 9/11. In this image, the overhead planes now celebrate the new buildings’ development.

- Body tracing from exhibit “Standing Tall.” Afterschool art therapy workshops were held at participating schools to build resiliency.

Q2: How do images help children understand and communicate their experience of the world around them?

A2: Creating art promotes sequential reasoning and organization of thought for those faced with overwhelming feelings but lacking the coping mechanisms to properly process them. This can be incredibly burdensome for children. I vividly recall my observations of children after the events of 9/11. Art was often the only way children could make sense of the insensible. Art can serve as a way to map pictorially that which cannot be examined verbally. Order can be visually established in the midst of psychological chaos. Art making aids in affect regulation and can transform a child in distress into an engaged artist. More recently, children are trying to understand the division in their classes and families. Loyalties are being questioned and anxieties are triggered amidst that uncertainty. Notably, more discussions in sessions echo themes of “us” versus “them”. The identity of the enemy “them” is interchangeable to whoever threatens their sense of safety. More children are hyperaroused and vigilant to protect their own vulnerabilities.

Q3: Given the current political climate, how can art help children communicate their anxieties to adults?

A3: Concretizing internalized feelings through art production can become a starting point for discussion and provide a visual record for further discussion. It is important for adults to empathetically respond to the child’s anxieties as evident in their narratives and images. Creating a safe and contained space (both visually and dynamically) will usher more authentic expression. A simple bordered paper gives the paper some visual containment. For older children, polarity drawings often help to highlight differences and similarities in opposing perspectives.

- A narrative of battling dinosaurs helps a child to describe experiences of victimization at home and at school.

- Child writes, “Never Mess with Good” to reaffirm his ability to defend against a bullying peer.

Q4: How can art therapy help develop empathy and possibly limit bullying in the school system?

A4: Art, in its continuum from more controlled to less controlled expression, can allow for experimenting in ways to cope with adversity. In the safe confines of the treatment relationship and through non-verbal expression, children can rehearse alternative paradigms of relatedness. The empowering quality of the non-verbal, creative process, a key underpinning of our work as art therapy professionals, enables clients to “visually speak” their expression, thereby mediating and containing their internalized struggles. Often, the bullied child creates scenes where he is a fiercely courageous superhero. The fantasy of overcoming adversity is first visualized and rehearsed in art therapy so that it can become more of a reality.

School-based art therapy is also a rich arena to promote “critical consciousness” as postulated by Paolo Freire (2005). In art therapy, students can reflect deeply about themselves in relation to their social climate, explore inherent contradictions in those relationships and become empowered to problem solve. The awareness, empowerment and accountability of Freire’s work in the context of oppression is quite relevant to our current work as art therapists.

In conclusion, art provides children a way to communicate thoughts or feelings that may seem too dangerous or too complex to spell out with words. The presence of art therapy services in one of the most familiar settings for children— the school— can promote safety in times of uncertainty, trauma, or conflict. School-based art therapy programs align directly with the AATA’s Vision of a world where “the services of licensed, culturally proficient art therapists are available to all individuals, families, and communities.” To view more images created by children in schools, visit our digital exhibition, “I am a work of art,” which celebrates the important role of art and creativity in mental health, wellness, and social-emotional well-being for our children, youth, and young adults.

Images were obtained with permissions, courtesy of the NYU Art Therapy in Schools Program.

References

Freire, P. (2005). Education for Critical Consciousness. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group.