By Rosemarie Rogers, ATR-BC, LCAT | November 11, 2015 | Veterans | Trauma

Art is a visual language. Human beings have been using art for this purpose for thousands of years. The cave paintings discovered in Lascaux, France and Picasso’s Guernica are celebrated examples. Visual arts offer veterans suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) a nonthreatening alternative to compose in images what is inexpressible to them with words. It is a way in and often the first step to organize and express overwhelming feelings and sensations they experience. Most importantly, their own artwork becomes the narrative to tell their story and is the foundation that we use to begin therapy.

The image to the right is an example of a veteran’s first artwork. He was deployed six times within an 8-year period to Iraq and Afghanistan and with no prior art experience he chose to work in clay. He created this piece with incredible detail and accuracy. After reflecting on the work he shook his head and stated: “I carry many memories on my back.” Through his art making he became engaged in the process of understanding the complex emotions around his combat medic experiences. As he stated on numerous occasions with this and other art works he made, “There are so many conflicting emotions.”

The image to the right is an example of a veteran’s first artwork. He was deployed six times within an 8-year period to Iraq and Afghanistan and with no prior art experience he chose to work in clay. He created this piece with incredible detail and accuracy. After reflecting on the work he shook his head and stated: “I carry many memories on my back.” Through his art making he became engaged in the process of understanding the complex emotions around his combat medic experiences. As he stated on numerous occasions with this and other art works he made, “There are so many conflicting emotions.”

When veterans first come to the art room I explain what art therapy is, how creativity and using one’s imagination are resources that are distinctly individual, that they come from within each of us and can help them to understand the issues that bring them to treatment. After some time has passed, I encourage the veterans to show their artwork to other therapists they are working with. Doing so often presents the clinician with another side of his/her client, as well as offers a way to find the verbal language necessary for talk therapy. After the artwork is created, I ask the veterans to add a writing component as a way for them to develop the language and to have a deeper understanding of what their experiences meant to them. Often, this takes the form of poetry.

Each war conflict presents its own set of problems for the returning soldiers. For example, the Vietnam veterans, many of whom were drafted at the age of 19 and who left the United States as naïve teenagers, returned to a country that had made a huge cultural/social shift. They did not receive a warm “welcome home”; few US citizens had “support the troops” decals on their cars. Instead, most were shunned, spit upon, and accused of being “baby killers.”

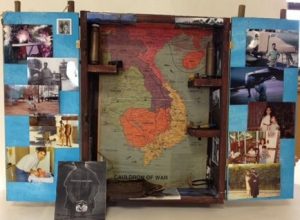

I was asked by a psychologist, Dr. Barbara Viegner-Smith, at the VA if I would like to collaborate on a project using art with two of her Vietnam veteran combat groups. She felt most of the veterans had hit a wall talking in groups. Collaboration with a psychologist who veterans had established a therapeutic relationship with was critical for the success of the project. The question I asked myself was, how does one ethically ask veterans to go back 40 years and express their combat trauma safely in a meaningful, beneficial way? Asking them to paint a picture of their combat experience would have sent them all out door, never to return. I had to present the project and build trust. The art material chosen was wood. We decided that constructing a box that could contain and “hold” whatever memories they chose using wood and nails made this project more accessible for veterans who were quite comfortable working with their hands, as most of them were carpenters, laborers, or postmen. In addition, it allowed them to create something they could bring home and share with their families, or store away in an attic or closet for posterity. I began with an education piece; the work of artist Joseph Cornell, who recreated worlds in shadow boxes, was presented to the veterans to provide a context for the work they were about to begin.

The construction of the box was like a ritual, and as the men worked they talk about their memories, the process, feelings of “us vs. them”, isolation. Anger emerged as a result and it became clear that more work had to be done. We asked them to create two other panels, one that expressed what it felt like when they returned home, and the other that expressed what was it like to create this box and how they feel in the here and now. We brought the two groups together; we read poems and excerpts from books written by Vietnam Veterans. We asked them to put into words what they had previously been unable to express.

To expand a sense of community, the boxes were exhibited at a community college on Veteran’s Day, where a community outside of the VA warmly accepted them. A book was left for civilians to write in their responses to the work and this acted as a keepsake as well as a challenge to the veterans’ notions about a community that didn’t care. After that, the veterans and therapists were invited to share/teach about the Vietnam War to high school students. It was a powerful conversation that helped the veterans gain respect from another generation that they didn’t originally receive from their own. Sometime later, without our involvement, veterans were asked to participate in a photo project with high school seniors and a YouTube video titled “First Annual Veterans Living History Project” was born.